Quick Overview

Associated References

Main Article

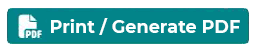

Lignocaine, also known as lidocaine, is a local anesthetic that plays a crucial role in wound care by providing effective pain relief. Understanding its mechanism of action is essential for clinicians to optimize its use in various clinical scenarios. Lignocaine primarily acts by inhibiting voltage-gated sodium channels in neuronal membranes, which is fundamental to its anesthetic properties. When lignocaine is administered, it diffuses across the neuronal membrane and binds to the intracellular portion of the sodium channels. This binding stabilizes the channel in an inactivated state, preventing the influx of sodium ions that is necessary for the generation and propagation of action potentials. As a result, the transmission of pain signals from the site of injury to the central nervous system is effectively blocked, leading to localized anesthesia (Lee et al., 2008).

In addition to its primary action on sodium channels, lignocaine has been shown to exert anti-inflammatory effects, which can be particularly beneficial in wound care. Research indicates that lignocaine may inhibit the activation of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4), a key player in the inflammatory response. TLR-4 is activated by pathogen-associated molecular patterns, such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS), leading to the activation of downstream signaling pathways, including nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) (Lee et al., 2008). By inhibiting TLR-4, lignocaine can reduce the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, thereby modulating the inflammatory response and potentially enhancing the healing process in wounds.

Moreover, lignocaine’s action is not limited to pain relief and inflammation modulation; it also influences the excitability of sensory neurons. Studies have demonstrated that lignocaine selectively blocks late sodium currents in sensory neurons, which are associated with the generation of ectopic impulses. This effect is particularly relevant in the context of neuropathic pain, where abnormal neuronal excitability contributes to persistent pain sensations (Baker, 2000). By targeting these late sodium currents, lignocaine can help alleviate neuropathic pain associated with chronic wounds, further supporting its role in wound care management.

The pharmacokinetics of lignocaine also play a significant role in its effectiveness as a local anesthetic. Lignocaine is rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream when administered via injection or topical application, with peak plasma concentrations typically occurring within 30 minutes. The drug is metabolized primarily in the liver, and its half-life ranges from 1.5 to 2 hours, depending on individual patient factors such as liver function (Orlando et al., 2003). Understanding these pharmacokinetic properties is essential for clinicians to determine appropriate dosing regimens and avoid potential toxicity, especially in patients with compromised liver function.

Furthermore, lignocaine’s formulation can influence its efficacy and safety profile. For instance, the addition of epinephrine to lignocaine formulations can prolong the duration of anesthesia by causing local vasoconstriction, which reduces systemic absorption and prolongs the drug’s action at the site of administration (Farnham & Pilowsky, 2009). This combination is particularly useful in surgical settings where extended pain relief is desired. However, clinicians must be cautious when using epinephrine in areas with end-arterial blood supply, such as fingers or toes, to avoid ischemic complications.

In summary, lignocaine’s mechanism of action in wound care is multifaceted, involving the blockade of sodium channels, modulation of inflammatory responses, and alteration of neuronal excitability. These combined effects contribute to its effectiveness as a local anesthetic and its utility in managing pain associated with wound care procedures. Clinicians must consider these mechanisms, along with pharmacokinetic factors and formulation choices, to optimize lignocaine’s use in clinical practice.

References:

- Baker, M. (2000). Selective block of late na+ current by local anaesthetics in rat large sensory neurones. British Journal of Pharmacology, 129(8), 1617-1626. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0703261

- Dissemond, J., Böttrich, J., Braunwarth, H., Hilt, J., Wilken, P., & Münter, K. (2017). Evidence for silver in wound care – meta‐analysis of clinical studies from 2000– JDDG Journal Der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft, 15(5), 524-535. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddg.13233

- Farnham, M. and Pilowsky, P. (2009). Local anaesthetics for acute reversible blockade of the sympathetic baroreceptor reflex in the rat. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 179(1), 58-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.01.012

- Lee, P., Tsai, P., Ya, H., & Huang, C. (2008). Inhibition of toll‐like receptor‐4, nuclear factor‐κb and mitogen‐activated protein kinase by lignocaine may involve voltage‐sensitive sodium channels. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology, 35(9), 1052-1058. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1681.2008.04962.x

- Nímia, H., Carvalho, V., Isaac, C., Souza, F., Gemperli, R., & Paggiaro, A. (2019). Comparative study of silver sulfadiazine with other materials for healing and infection prevention in burns: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Burns, 45(2), 282-292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2018.05.014

- Orlando, R., Piccoli, P., Martin, S., Padrini, R., & Palatini, P. (2003). Effect of the cyp3a4 inhibitor erythromycin on the pharmacokinetics of lignocaine and its pharmacologically active metabolites in subjects with normal and impaired liver function. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 55(1), 86-93. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01718.x

- Pavlík, V., Sobótka, L., Pejchal, J., Čepa, M., Nešporová, K., Arenbergerová, M., … & Velebný, V. (2021). Silver distribution in chronic wounds and the healing dynamics of chronic wounds treated with dressings containing silver and octenidine. The Faseb Journal, 35(5). https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.202100065r

- Pham, C., Collier, Z., Fang, M., Howell, A., & Gillenwater, T. (2019). The role of collagenase ointment in acute burns: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Wound Care, 28(Sup2), S9-S15. https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2019.28.sup2.s9

- Ren, S., Liu, Y., Zhu, G., Li, M., Shi, S., Ren, X., … & Gao, R. (2020). Strategies and challenges in the treatment of chronic venous leg ulcers. World Journal of Clinical Cases, 8(21), 5070-5085. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i21.5070