Quick Overview

Associated References

Main Article

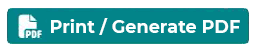

Chlorhexidine acetate is a widely used antiseptic in wound care, with a history that dates back to its synthesis in the 1950s. Initially developed for surgical antisepsis, chlorhexidine’s application has expanded significantly over the decades. It became prominent in various healthcare settings due to its broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, particularly against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. The compound is now integral to protocols aimed at preventing infections in surgical wounds, chronic wounds, and during invasive procedures such as catheter insertions. Its introduction into wound care management has been pivotal in reducing infection rates and improving patient outcomes O’Grady et al. (2011).

The mechanism of action of chlorhexidine acetate is primarily based on its ability to disrupt microbial cell membranes. Chlorhexidine binds to the negatively charged components of bacterial cell walls, leading to increased permeability and subsequent cell lysis. This action is effective against a wide range of pathogens, including bacteria and fungi, making chlorhexidine a versatile antiseptic in wound care (Viray et al., 2014). Moreover, chlorhexidine exhibits a property known as substantivity, which allows it to remain active on the skin and in the wound bed for extended periods. This prolonged antimicrobial activity is particularly beneficial in preventing infections in chronic wounds, where the risk of bacterial colonization is high (Schlett et al., 2014).

Despite its advantages, the use of chlorhexidine acetate in wound care requires careful consideration of several precautions. One significant concern is the potential for skin irritation and allergic reactions, particularly in sensitive individuals. Healthcare providers must assess patients for any history of hypersensitivity to chlorhexidine before application. Additionally, chlorhexidine should not be used in conjunction with certain other antiseptics, such as iodophors, as this can lead to reduced efficacy and increased risk of skin irritation (Viray et al., 2014). Another critical consideration is the emergence of chlorhexidine-resistant strains of bacteria, particularly methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Studies have indicated that prolonged exposure to chlorhexidine can lead to the selection of resistant strains, necessitating careful monitoring and judicious use of this antiseptic in clinical practice (Schlett et al., 2014).

The historical context of chlorhexidine acetate’s application in wound care highlights its evolution from a surgical antiseptic to a vital component of modern wound management protocols. In recent years, there has been a growing body of evidence supporting its use in various clinical settings, including long-term care facilities and outpatient wound clinics. Research has demonstrated that chlorhexidine bathing can significantly reduce the incidence of healthcare-associated infections, particularly in patients colonized with MRSA. This has led to the incorporation of chlorhexidine into infection control bundles, emphasizing its role in preventing cross-contamination and promoting patient safety (Jeffries et al., 2009).

In addition to its antimicrobial properties, chlorhexidine acetate has been shown to enhance wound healing through its effects on the inflammatory response. By modulating the activity of inflammatory cells, chlorhexidine can help create a more favorable environment for tissue regeneration. This aspect is particularly important in the management of chronic wounds, where inflammation can impede healing and lead to further complications (Chaiyakunapruk et al., 2003). The integration of chlorhexidine into advanced wound dressings, such as hydrocolloids and alginates, has further optimized its delivery, ensuring sustained antimicrobial activity while providing a moist wound environment conducive to healing (Chaiyakunapruk et al., 2003).

The application of chlorhexidine acetate in wound care is supported by a robust body of literature. Recent studies have highlighted its effectiveness in reducing bacterial load in various wound types, including diabetic ulcers, pressure sores, and surgical wounds. For instance, a systematic review found that chlorhexidine-impregnated dressings significantly decreased the incidence of infection compared to standard dressings (Bruwer, 2024). Moreover, the use of chlorhexidine in preoperative skin preparation has been associated with lower rates of surgical site infections, underscoring its importance in surgical wound management (Azzawi et al., 2016).

Chlorhexidine’s role in infection control extends beyond wound care. It has been incorporated into guidelines for preventing intravascular catheter-related infections, where its use as a skin antiseptic has been shown to reduce the incidence of catheter-related bloodstream infections (McAlearney et al., 2015). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends the use of chlorhexidine for skin preparation prior to catheter insertion, emphasizing its importance in infection control protocols (McAlearney et al., 2015). Furthermore, chlorhexidine bathing has been identified as a critical intervention in reducing the transmission of multidrug-resistant organisms in healthcare settings (Holland & McBride, 2013).

In conclusion, chlorhexidine acetate remains a critical active ingredient in wound care, with a well-established history and a mechanism of action that supports its efficacy as an antimicrobial agent. While precautions regarding its use are necessary to mitigate potential adverse effects and resistance issues, the benefits it offers in preventing infections and promoting healing are substantial. As the field of wound care continues to evolve, ongoing research will be essential to further elucidate the optimal use of chlorhexidine acetate and to develop strategies to combat resistance, ensuring that this valuable antiseptic remains a mainstay in clinical practice.

References:

- Alhmidi, H., Cadnum, J., Koganti, S., Jencson, A., Rutter, J., Wilson, B., … & Donskey, C. (2019). Shedding of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus by colonized patients during procedures and patient care activities. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 40(3), 328-332. https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2018.342 , Accessed 28/12/2024

- Azzawi, M., Seifalian, A., & Ahmed, W. (2016). Nanotechnology for the diagnosis and treatment of diseases. Nanomedicine, 11(16), 2025-2027. https://doi.org/10.2217/nnm-2016-8000, Accessed 28/12/2024

- Bruwer, F. (2024). Amniotic membrane in the treatment of hard-to-heal wounds.. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.1004843, Accessed 28/12/2024

- Chaiyakunapruk, N., Veenstra, D., Lipsky, B., Sullivan, S., & Saint, S. (2003). Vascular catheter site care: the clinical and economic benefits of chlorhexidine gluconate compared with povidone iodine. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 37(6), 764-771. https://doi.org/10.1086/377265, Accessed 28/12/2024

- Fu, L. (2016). Delivery systems in wound healing and nanomedicine.. https://doi.org/10.5772/63763, Accessed 28/12/2024

- Gall, E., Long, A., & Hall, K. (2020). Chlorhexidine bathing strategies for multidrug-resistant organisms: a summary of recent evidence. Journal of Patient Safety, 16(3), S16-S22. https://doi.org/10.1097/pts.0000000000000743, Accessed 28/12/2024

- Gomes, G. (2024). Chlorhexidine and prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia: an integrative review of vap incidence and mortality.. https://doi.org/10.56238/sevened2024.003-068, Accessed 28/12/2024

- Holland, A. and McBride, C. (2013). Non‐operative advances: what has happened in the last 50 years in paediatric surgery?. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 51(1), 74-77. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.12461 , Accessed 28/12/2024

- Jeffries, H., Mason, W., Brewer, M., Oakes, K., Muñoz, E., Gornick, W., … & Jarvis, W. (2009). Prevention of central venous catheter-associated bloodstream infections in pediatric intensive care units a performance improvement collaborative. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 30(7), 645-651. https://doi.org/10.1086/598341 , Accessed 28/12/2024

- McAlearney, A., Hefner, J., Robbins, J., Harrison, M., & Garman, A. (2015). Preventing central line–associated bloodstream infections: a qualitative study of management practices. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 36(5), 557-563. https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2015.27 , Accessed 28/12/2024

- Nadelmann, E. and Czernik, A. (2018). Wound care in immunobullous disease.. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.71937, , Accessed 28/12/2024

- O’Grady, N., Alexander, M., Burns, L., Dellinger, E., Garland, J., Heard, S., … & Saint, S. (2011). Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. American Journal of Infection Control, 39(4), S1-S34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2011.01.003 , Accessed 28/12/2024

- Parwani, L., Shrivastava, M., & Singh, J. (2022). Potential of cyanobacteria in wound healing.. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.98521 , Accessed 28/12/2024

- Peterson, L., Boehm, S., Beaumont, J., Patel, P., Schora, D., Peterson, K., … & Smith, B. (2016). Reduction of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus infection in long-term care is possible while maintaining patient socialization: a prospective randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Infection Control, 44(12), 1622-1627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2016.04.251 , Accessed 28/12/2024

- Rhee, S., Vallé, M., Wilson, L., Lazarus, G., Zenilman, J., & Robinson, K. (2015). Negative pressure wound therapy technologies for chronic wound care in the home setting: a systematic review. Wound Repair and Regeneration, 23(4), 506-517. https://doi.org/10.1111/wrr.12295 , Accessed 28/12/2024

- Schlett, C., Millar, E., Crawford, K., Cui, T., Lanier, J., Tribble, D., … & Ellis, M. (2014). Prevalence of chlorhexidine-resistant methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus following prolonged exposure. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 58(8), 4404-4410. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.02419-14 , Accessed 28/12/2024

- Schlett, C., Millar, E., Crawford, K., Cui, T., Lanier, J., Tribble, D., … & Ellis, M. (2014). Prevalence of chlorhexidine-resistant methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus following prolonged exposure. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 58(8), 4404-4410. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.02419-14 , Accessed 28/12/2024

- Teixeira, M., Amorim, M., & Felgueiras, H. (2019). Cellulose acetate in wound dressings formulations: potentialities and electrospinning capability., 1227-1230. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-31635-8_149 , Accessed 28/12/2024

- Viray, M., Morley, J., Coopersmith, C., Kollef, M., Fraser, V., & Warren, D. (2014). Daily bathing with chlorhexidine-based soap and the prevention of staphylococcus aureus transmission and infection. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 35(3), 243-250. https://doi.org/10.1086/675292 , Accessed 28/12/2024